City Know-hows

Share

Target audience

Managers of public space. City planners, urban designers, landscape architects and architects in Europe and Latin America and North America and Australasia. Lead urban designers in city government.

The problem

COVID-19 is changing how we use public space and this may have lasting consequences for our cities. Many conjectures, predictions and hypothesis are being made, but the future is highly uncertain. While it is too early to predict how city design will change, it is urgent to begin to outline the key dimensions of this discussion and consider how built environment related professions and practice will need to change or adapt.

What we did and why

We reviewed many of the ways in which cities might be adapting to the COVID-19 crisis with a focus on public space – use, design and management. While it is too early to predict how city design will change, it is worthwhile to begin to outline the key dimensions of this discussion and consider how our profession and practice will need to change or adapt.

Our study’s contribution

We summarize the main ways in which the COVID-19 crisis might change our relationship with public space. We think beyond the current measures to consider which changes will stay with us once the immediacy of the pandemic has passed. The size, scope and speed of the crisis make it feel like we are living through a profound transformation. It is as if we are experiencing a tectonic shift, where the ground is moving beneath us, changing the fundamental principles and rules that have governed our practice. Will 2020 define a before and after in planning and design?

Impacts for city policy and practice

While there are many potential impacts of COVID-19 on land use, urban density, telecommuting, energy, transportation, retail, and so forth, our focus is on how the current pandemic may change public space. Our list of emerging questions is extensive but not exhaustive. We do not have all the answers now. As a result, we will need to observe, measure and reflect on changing patterns in the use of public space. Things are moving fast.

We identify important questions emerging from our experiences of the COVID-19 episode that may change the ‘Use, Behaviour and Perceptions’ (nine questions) and ‘Design’ (five questions). We pose another five questions for inequities and exclusion:

How will the needs of vulnerable groups such as racial minorities, immigrants, women, the poor, elderly, children, disabled and the homeless be accounted for in future public space designs, practices, and rules?

Will cities in the Global South attempt to constrain further or regulate the informal street economy?

Will COVID-19 change who moves in and who moves out of newly redeveloped urban centers?

Will everyone be able to shift to active transit?

Will the pandemic permanently disrupt the interconnected global settlement system and freedom of movement?

Further information

Urban Planning, Environment and Health at The Barcelona Institute for Global Health, ISGlobal. An aim is to strengthen the connection between the health of the population and the environment as the foundation for urban planning

Barcelona Lab for Urban Environmental Justice and Sustainability. The Lab develops research on environmental justice and sustainability that builds on urban planning, policy, and studies in social inequality and development.

Full research article:

The impact of COVID-19 on public space: an early review of the emerging questions – design, perceptions and inequities by Jordi Honey-Rosés, Isabelle Anguelovski, Vincent K. Chireh, Carolyn Daher, Cecil Konijnendijk van den Bosch, Jill S. Litt, Vrushti Mawani, Michael K. McCall, Arturo Orellana, Emilia Oscilowicz, Ulises Sánchez, Maged Senbel, Xueqi Tan, Erick Villagomez, Oscar Zapata & Mark J Nieuwenhuijsen.

Related posts

Beaches can be important settings for physical activity. The quality of these spaces (safety, amenities, aesthetics) can influence how well they support physical activity and health. The quality of beaches may differ across neighbourhoods, with higher socioeconomic status neighbourhoods having disproportionately better access to beaches.

Urban planners, economists, health and community policymakers and practitioners share insights in a new study on creating healthy food environments using urban planning policy and governance levers.

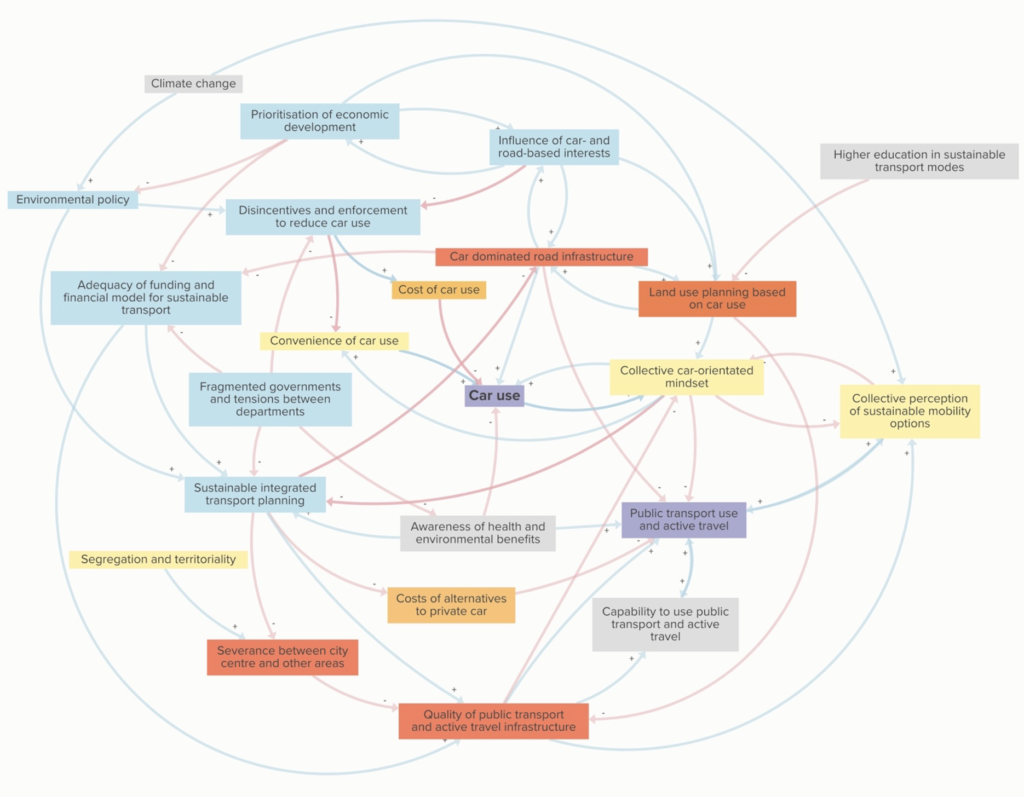

Belfast has very high levels of car use. Working with stakeholders we tried to understand what factors influence this. System wide factors, such as financial models for transport, a collective car-orientated mindset and car dominated road infrastructure, have the strongest influence on individual behaviour.