City Know-hows

Health impact assessments are a key tool to bridge the worlds of planning and health, but there’s a risk they become a ‘tick box’ exercise with little real-world benefit. Learning from recent practice in English local authorities can help maximise their effectiveness in producing healthier developments.

Share

Target audience

City planning and public health officers, developers and consultants responsible for commissioning or undertaking health impact assessments on new projects.

The problem

The built environment has a big impact on health and wellbeing. Health impact assessments are one tool used to deliver healthier developments, involving assessing the likely impact of a development project on health. They are used globally and increasingly in England, but we know relatively little about how this is going in practice. We also need to know how they interact with urban planning decision-making processes to deploy them most effectively.

What we did and why

We conducted interviews with stakeholders involved in planning projects: city public health officers, health impact assessment consultants and a national policymaker. A variety of perspectives were sought to give a more rounded view of how things work. Some locations chosen had been using health impact assessments for some time, while were newer to using health impact assessments. Insights from policy theory and health impact assessment theory were used to make sense of the data.

Our study’s contribution

Stakeholders consider health impact assessments a valuable, if limited, tool to improve health and address inequalities. Health impact assessments work by forcing change on developers through regulation, but more so by persuading developers of the case for healthier places to improve the health impact of developments voluntarily. This account can help stakeholders involved in health impact assessments understand and manage the process more effectively. The paper suggests ways to overcome key barriers to the effective use of health impact assessments.

Impacts for city policy and practice

City public health officers should:

1. Make sure health impact assessments are part of a wider health placemaking strategy based on a good understanding of how health impact assessments work to produce health. This means thinking hard about how to use the lever of health impact assessment to generate constructive dialogue between stakeholders, including developers and the community.

2. Focus on building understanding and relationships with planners first, and externally with developers and health impact assessment practitioners

3. Build in monitoring and evaluation of health impact assessments.

Further information

For further information:

Public Health England Health Impact Assessment guidance – provides a simple how-to for city officers on implementing Health Impact Assessments (England focus).

Research on Health Impact Assessments in planning practice in England – practical research reviewing a sample of Health Impact Assessments and drawing lessons.

Town and Country Planning Association – organisation with an active workstream on health and planning which produces resources and research (England focus).

Full research article:

Related posts

People living in informal settlements endure the disproportionate burden of health vulnerabilities due to poor living conditions, overcrowding and infrastructural neglect. I examine how social, economic, political and environmental forces converge to amplify health disparities in Harare’s informal settlements.

Integrating green spaces into urban planning is crucial for public health. This framework guides cities in evaluating and optimizing their green space strategies to promote health and sustainability, aligning with WHO’s Healthy Cities initiative.

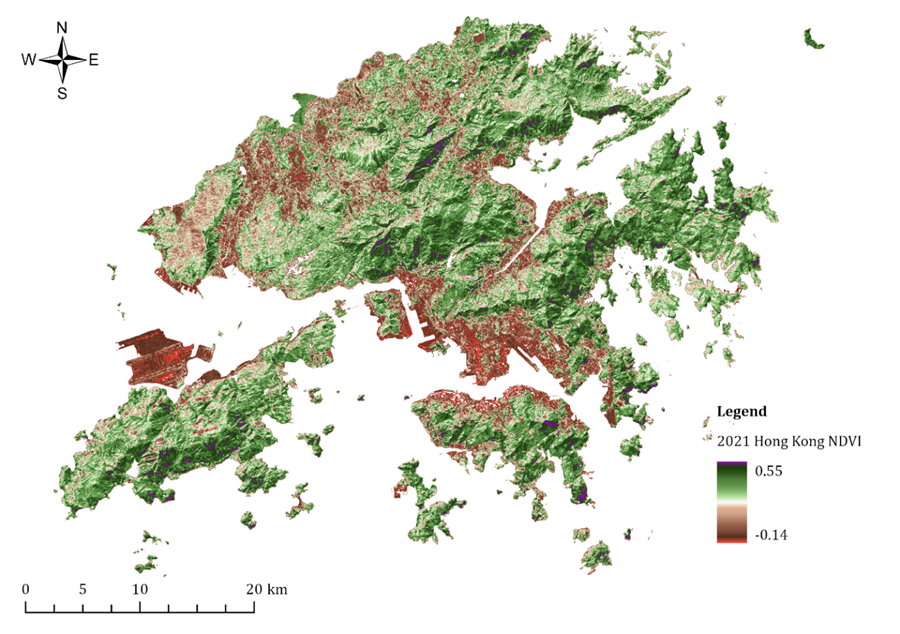

Residing in a neighbourhood with higher greenness within 400 metres was associated with higher residential greenspace visitations during the COVID-19 pandemic. Policies towards scaling up and optimising residential greenness may constitute important interventions for enhancing population-level resilience during public health emergencies.