City Know-hows

Extreme heat and wildfire smoke are a growing concern in cities. Cooling and cleaner air centres can provide a much-needed respite but too often they’re set up reactively and inconsistently. Our study explores what works, what doesn’t, and how cities can design these spaces to be reliable, inclusive, and accessible for all.

Share

Target audience

Municipal and provincial policymakers, public health officials, emergency management agencies, urban planners, civil society organisations.

The problem

Across North America, cities are scrambling to provide refuge during heatwaves and smoke events by designating “cooling and cleaner air centres.” But without clear planning, funding, or coordination, these centres are often underdelivering. The result? People most at risk seniors, unhoused residents, low-income families often cannot access the protection they need.

What we did and why

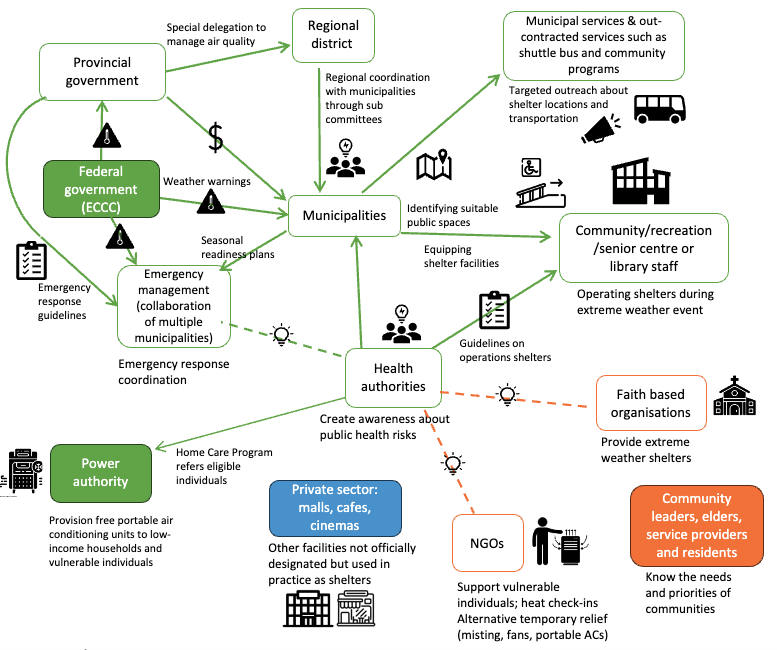

We reviewed academic and grey literature to see how other cities deploy cooling and cleaner air centres and what lessons they offer. Then, we spoke with 16 professionals from municipal governments, health authorities, and NGOs in Greater Vancouver to understand real-world challenges and opportunities. This research was co-designed with regional government partners to produce findings directly relevant to decision-makers while contributing to broader adaptation and equity research.

Our study’s contribution

We show that cleaner and cooler air centres work best when supported by long-term planning, secure funding, and strong partnerships between governments and community organisations. Our research highlights key barriers like gaps in outreach, poor site accessibility, and limited coordination and identifies promising practices to make these centres more inclusive and reliable. These findings are immediately relevant to cities grappling with rising heat and wildfire smoke while seeking to protect public health equitably.

Impacts for city policy and practice

Cities need to move beyond ad-hoc responses and embed cooling and cleaner air centres within comprehensive climate adaptation strategies. This means investing in infrastructure upgrades, improving site distribution and accessibility, expanding outreach to underserved populations, and creating clear governance frameworks for inter-agency collaboration. Cooling and cleaner air centres can be valuable assets if they are planned proactively, designed inclusively, and supported by long-term policy commitments.

Further information

Full research article:

Heat, smoke, and urban health: Cooling and cleaner air centres as a tool for adaptation in a Canadian urban region by Glory O. Apantaku, Ana Polgar, Felix Giroux, Amanda Giang, Derek Gladwin and Naoko Ellis.

Related posts

Livability is a people-oriented concept, and accurately measuring it requires a contextual understanding of what local stakeholders deem essential for making communities livable. Despite extensive research on livability indicators, most studies have taken a top-down approach, with few considering the input of the communities.

As the global urban population grows, food production and housing are currently ‘competing’ with each other for land on the edges of cities. Both essential urban components, this research supports town planning and urban design professionals to explore alternative peri-urban land use typologies, where food production and housing co-exist for greater urban health and resilience.

This study sheds light on Indian planners’ perceptions of health integration in urban and regional planning, highlighting implementation obstacles as well as acknowledgement of the topic’s significance.