City Know-hows

Environmental health in cities isn’t just about air quality and green spaces, it’s also about how people live, perceive and feel in their neighbourhoods. In Paris, residents voiced their concerns during planning meetings, revealing what truly matters to their well-being. We transformed their lived experiences into a model that city leaders can use.

Share

Target audience

Urban planning departments, city health officers, and participatory governance facilitators working on climate adaptation in cities.

The problem

Urban environmental health is often defined using general indicators like “liveability” or “sustainability.” But these miss the mark if they aren’t rooted in local context. In Paris, issues like noise, density, and unequal access to green spaces have a direct impact on how healthy people feel in their own streets and homes. We need a better way to assess and act on urban health, starting from the ground up.

What we did and why

I attended and analysed nine public meetings in Paris held as part of the bioclimatic revision of the local urban plan. My goal was to listen to what residents actually say when discussing health and environment. Using grounded theory, I built a model based on their lived experience. This model captures the real, local parameters shaping environmental health in the city. This approach brings people’s voices directly into policy design.

Our study’s contribution

This study introduces a place-based model of urban environmental health drawn from residents’ perspectives.

• Highlights eight interconnected local parameters of environmental health.

• Demonstrates that residents link environmental health to everyday nuisances like noise, air pollution, and lack of safety.

• Shows that viable and livable environments depend on inclusive governance and infrastructure decisions.

• Offers a replicable approach for other cities to assess urban health from the ground up.

Impacts for city policy and practice

This work invites planners and policymakers to rethink how they assess environmental health.

• Use participatory methods to identify local ‘nuisance hotspots’.

• Design planning rules that reduce noise and improve green space access.

• Promote equitable distribution of health-supportive infrastructures like sports or healthcare facilities.

• Integrate environmental health into local zoning and development decisions as a fundamental element.

Further information

Full research article:

Related posts

The high risk of death and disability from being struck by a car is unevenly distributed geographically and socially. Our analytics reveal a troubling pattern in that people from Black and Latino neighbourhoods facean especially high risk of crashes, both near and far from home.

Vision Zero leaders in the hundreds of participating cities across the world in planning departments, nonprofits, and community groups need to look at our approach.

Our Jerusalem Railway Park study addressed the needs of those aged 55 in disparate communities, with long-term implications for physical and mental health, and community

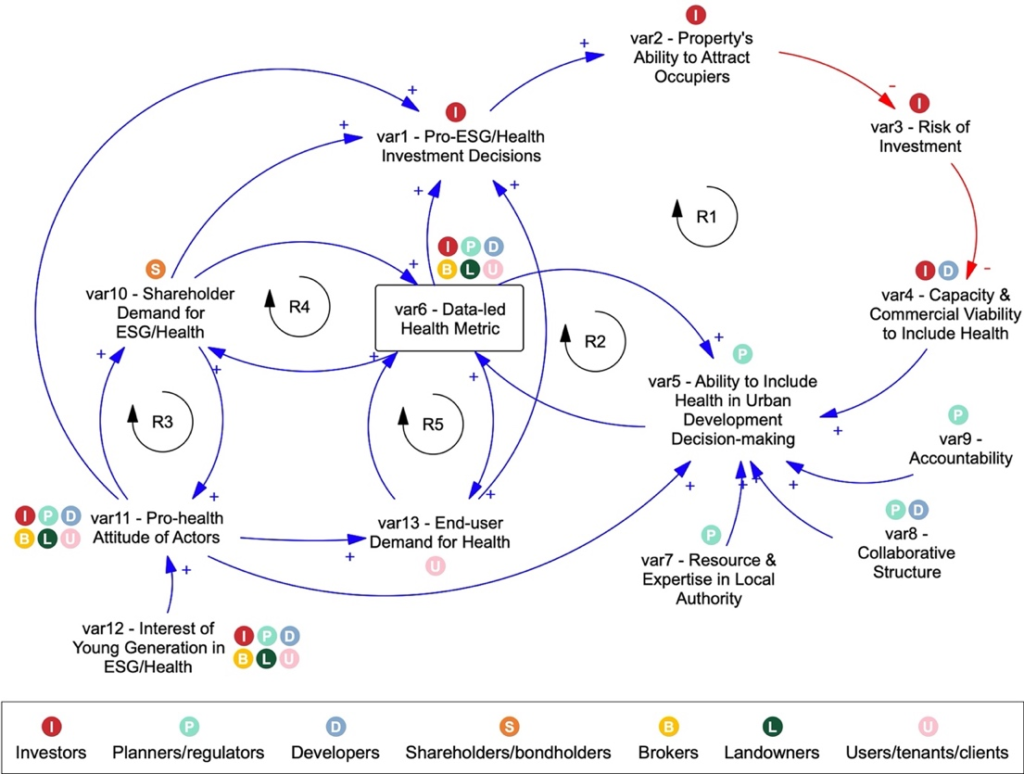

How can we systematically embed health in real estate decision-making to improve health outcomes related to our urban environment? We mapped the system of health consideration in urban development decision-making to identify leverage points and inform interventions that can generate virtuous feedback loops to support better urban health.